The richest one percent of this country owns half our country's wealth, five trillion dollars. One third of that comes from hard work, two thirds comes from inheritance, interest on interest accumulating to widows and idiot sons and what I do, stock and real estate speculation. It's bullshit. You got ninety percent of the American public out there with little or no net worth. I create nothing. I own.

Thursday, June 28, 2012

Two bonds that DoubleLine bought over $1.7bil of last month

While people tend to flock to the DoubleLine Capital conference calls, I’ve always been more interested in tracking the bonds that they buy from month to month. After all, with AUM in the Total Return Fund now exceeding $27bil, they need to be buying a TON of bonds. Where do they see value? How does that fit in with housing and macro views?

In retrospect, the fund has changed a lot over the past two plus years. When the fund opened in March of 2010 the 10yr was over 3.5%, and non-agency MBS prices were generally much lower across the board. With rivals fretting about “who will buy all of those treasuries”, DoubleLine prudently bought a large amount of duration in the form of last cash flow Z CMO’s at deep discounts. The key rate duration of these type of bonds were tied to the 10-30yr part of the UST curve, and they obviously rallied tremendously as the 10 & 30yr now sit at 1.66% and 2.75% respectively. Today’s rate environment is very different and so are the opportunities in fixed income.

The relatively stable loss-adjusted yields produced by non-agency MBS are still available, but they’ve come in with the overall yield chase. Furthermore, with billions going into the total return fund each month it becomes more difficult to source as attractive bonds as it was when the asset base was a fraction of today’s size.

What are they buying today with these massive inflows?

After reviewing the fund holdings of DBLTX as of May 31st, 2012, a few purchases were notable. DoubleLine added over $1bil of newly issued 20yr 3.5% pools and nearly $700mil of 30yr 4% jumbo pools. The 3.5% pools are borrowers with a rate of ~4%. Looking at total issuance for May, it appears DoubleLine bought about 1/3rd of the total issuance of these bonds. This collateral has been pretty slow with prepays generally under 10c. Not a super sexy bond, as it will likely yield somewhere in the 2.30%-2.60% range with a spread of ~1.35% over USTs, but the bond would be a strong performer if rates continue to fall and/or QE3 comes around.

Grantham: ho hum 7 yrs

Jeremy Grantham has attracted a cultlike following to his quarterly

investment letters. For good reason: The chief investment strategist at

Boston asset manager GMO warned of dismal returns ahead for U.S. stocks

in the 2000s and predicted the bursting of both the technology and

housing bubbles.

Lest you get the impression Grantham is a permabear (a label he hates), in his March 2009 letter he advised snapping up U.S. stocks just as they were plunging to their nadir in the financial crisis. Those who bought profited from one of the most powerful market rallies ever. N

These days Grantham, 73, is downbeat about the prospects for most, but not all, stocks. A student of history, he has much to say about why markets get out of whack, and why we may be entering a period in which resource scarcity is again an issue for society -- and an opportunity for investors.

How do you go about finding the best opportunities?

The great opportunities are much more likely to come at the broader asset class level than from individual stocks.

Asset classes -- stocks, bonds, commodities -- get very badly mispriced. That's because they come with enormous career risks for institutional investors. As a professional, you can afford to pick some stocks and be wrong about a few of them. To keep your job, you cannot take the risk of being seen to be wrong about the "big picture" for very long.

How did the price/earnings ratio of the S&P 500 get to 35 in 2000, compared with the long-run average of 15?

You had a massively mispriced market, and it was talked about all over the place. But no one would step aside. Institutions couldn't bring themselves to do that because they would have been skinned alive for their conservatism.

So asset allocation is an enormous opportunity, but only if you're willing to take considerable career risks. Playing against the tech bubble was unbelievably painful for us for two years, and then eventually, of course, it paid off handsomely.

How do you avoid getting sucked into bubbles yet still get some benefit from rising prices?

Remember that history always repeats itself. Every great bubble in history has broken. There are no exceptions.

At GMO, we have a database of 35 bubbles. Of the 33 that have ended, every one broke all the way back -- not halfway back -- to the trend before the bubble started.

Remember also that stocks are kind enough to wear a price tag. In 2000 the price tag said "Ouch!" It implied a return of negative 3% a year for 10 years. In March 2009 the price tag for the S&P 500 was 13 times earnings. That said you were going to make about 10% a year plus inflation for seven years.

Is a bubble forming in the U.S. bond market?

Fixed income has had a big run for two reasons. One is manipulation by the Federal Reserve to keep rates artificially low. The other is the substantial degree of nervousness in the system due to the weak economy, Europe's problems, and the recency of the great crash. So you have in fixed income what I would call an anti-bubble. It's there because people are still frightened of the stock market.

The next giant move in bonds will be bad for long-term-bond holders. The normal return would be 3% plus inflation. So if inflation is around 2.5%, you'd expect 5.5% from a government bond. That's a long, long way from where we are.

What is the long-term effect of the Federal Reserve keeping interest rates low?

[Fed chairman Ben] Bernanke is making sure that we don't get a decent risk-free return. It's brutally unfair to retirees. He's doing this because if he keeps rates ugly enough for long enough, we will reluctantly filter our money into equities. A higher stock market induces more consumption and is helpful short term to the economy.

The bad news is every penny of that gets given back. It's like a pact with the devil: You make your money by pushing stocks up, but then inevitably the market must go back to fair value. When it does, it creates an anti-wealth effect, usually at the worst possible time.

What is your long-term outlook for stocks?

Returns over the next seven years will likely be ho-hum. On a global portfolio, that means maybe 4% after inflation, compared with 6.1% historically.

What area of the world do you see as a focus for investment over the next few years?

Foreign markets are decidedly more reasonable than the U.S., so we advise a bigger than normal emphasis on developed and emerging countries. They're priced to return about 5.1% a year, above inflation, over seven years.

Within the U.S., 100% of our equities are in high-quality blue chips. If you concentrate on the great franchise companies, you should get a real return of around 3.9% over seven years. So you'll feel not too bad.

Our seven-year numbers say that you should stay away from low-quality U.S. equities completely.

If you're underweight U.S. stocks, is it because you see another bubble there?

It doesn't feel to me that we're in the late stages of a bubble. The U.S. seems overpriced -- and if you take out the blue chips, it seems substantially overpriced. But it doesn't have the usual signs of group-think.

If the S&P 500 were to build up from about 1300 today to 1500 later this year or early next, then you'd want to run for cover and keep your head down.

Are commodities the next bubble? -

We used to live in a world where the price of resources came down steadily, and now the world has changed. You have a great mismatch between finite resources and exponential population growth.

China uses 46% of all the world's coal, for heaven's sake! The global population has surged from 6 billion to 7 billion in 12 years, and is now on its way to 9 billion. You'd better expect prices to rise.

So how would you advise investing in commodities?

I wouldn't touch futures; it's complicated and too unprofitable. Buy the guys who own stuff in the ground. Metal, oil, even natural gas, which is cheap now but will eventually pick up.

Our biggest problem as a planet will be our inability to feed more than 9 billion people in 30 years' time. We have to address this. It's much more important than any stock market problems.

When it comes to portfolios, my personal advice is for anyone who can, put money into forestry or farmland. Long term, you would probably never come near their returns in the stock market. In the world that I see, land is golden.

How will the stock market react to the upcoming election?

On one hand you've still got Bernanke promising to keep rates low. On the other hand, you've entered a new political world. The Republicans will want to show much more fiscal responsibility. And even if the Democrats are back, they will attempt to illustrate that they are also aware of the long-term problems of debt accumulation. My guess is that it's a tougher environment for the market starting next year.

Lest you get the impression Grantham is a permabear (a label he hates), in his March 2009 letter he advised snapping up U.S. stocks just as they were plunging to their nadir in the financial crisis. Those who bought profited from one of the most powerful market rallies ever. N

These days Grantham, 73, is downbeat about the prospects for most, but not all, stocks. A student of history, he has much to say about why markets get out of whack, and why we may be entering a period in which resource scarcity is again an issue for society -- and an opportunity for investors.

How do you go about finding the best opportunities?

The great opportunities are much more likely to come at the broader asset class level than from individual stocks.

Asset classes -- stocks, bonds, commodities -- get very badly mispriced. That's because they come with enormous career risks for institutional investors. As a professional, you can afford to pick some stocks and be wrong about a few of them. To keep your job, you cannot take the risk of being seen to be wrong about the "big picture" for very long.

How did the price/earnings ratio of the S&P 500 get to 35 in 2000, compared with the long-run average of 15?

You had a massively mispriced market, and it was talked about all over the place. But no one would step aside. Institutions couldn't bring themselves to do that because they would have been skinned alive for their conservatism.

So asset allocation is an enormous opportunity, but only if you're willing to take considerable career risks. Playing against the tech bubble was unbelievably painful for us for two years, and then eventually, of course, it paid off handsomely.

How do you avoid getting sucked into bubbles yet still get some benefit from rising prices?

Remember that history always repeats itself. Every great bubble in history has broken. There are no exceptions.

At GMO, we have a database of 35 bubbles. Of the 33 that have ended, every one broke all the way back -- not halfway back -- to the trend before the bubble started.

Remember also that stocks are kind enough to wear a price tag. In 2000 the price tag said "Ouch!" It implied a return of negative 3% a year for 10 years. In March 2009 the price tag for the S&P 500 was 13 times earnings. That said you were going to make about 10% a year plus inflation for seven years.

Is a bubble forming in the U.S. bond market?

Fixed income has had a big run for two reasons. One is manipulation by the Federal Reserve to keep rates artificially low. The other is the substantial degree of nervousness in the system due to the weak economy, Europe's problems, and the recency of the great crash. So you have in fixed income what I would call an anti-bubble. It's there because people are still frightened of the stock market.

The next giant move in bonds will be bad for long-term-bond holders. The normal return would be 3% plus inflation. So if inflation is around 2.5%, you'd expect 5.5% from a government bond. That's a long, long way from where we are.

What is the long-term effect of the Federal Reserve keeping interest rates low?

[Fed chairman Ben] Bernanke is making sure that we don't get a decent risk-free return. It's brutally unfair to retirees. He's doing this because if he keeps rates ugly enough for long enough, we will reluctantly filter our money into equities. A higher stock market induces more consumption and is helpful short term to the economy.

The bad news is every penny of that gets given back. It's like a pact with the devil: You make your money by pushing stocks up, but then inevitably the market must go back to fair value. When it does, it creates an anti-wealth effect, usually at the worst possible time.

What is your long-term outlook for stocks?

Returns over the next seven years will likely be ho-hum. On a global portfolio, that means maybe 4% after inflation, compared with 6.1% historically.

What area of the world do you see as a focus for investment over the next few years?

Foreign markets are decidedly more reasonable than the U.S., so we advise a bigger than normal emphasis on developed and emerging countries. They're priced to return about 5.1% a year, above inflation, over seven years.

Within the U.S., 100% of our equities are in high-quality blue chips. If you concentrate on the great franchise companies, you should get a real return of around 3.9% over seven years. So you'll feel not too bad.

Our seven-year numbers say that you should stay away from low-quality U.S. equities completely.

If you're underweight U.S. stocks, is it because you see another bubble there?

It doesn't feel to me that we're in the late stages of a bubble. The U.S. seems overpriced -- and if you take out the blue chips, it seems substantially overpriced. But it doesn't have the usual signs of group-think.

If the S&P 500 were to build up from about 1300 today to 1500 later this year or early next, then you'd want to run for cover and keep your head down.

Are commodities the next bubble? -

We used to live in a world where the price of resources came down steadily, and now the world has changed. You have a great mismatch between finite resources and exponential population growth.

China uses 46% of all the world's coal, for heaven's sake! The global population has surged from 6 billion to 7 billion in 12 years, and is now on its way to 9 billion. You'd better expect prices to rise.

So how would you advise investing in commodities?

I wouldn't touch futures; it's complicated and too unprofitable. Buy the guys who own stuff in the ground. Metal, oil, even natural gas, which is cheap now but will eventually pick up.

Our biggest problem as a planet will be our inability to feed more than 9 billion people in 30 years' time. We have to address this. It's much more important than any stock market problems.

When it comes to portfolios, my personal advice is for anyone who can, put money into forestry or farmland. Long term, you would probably never come near their returns in the stock market. In the world that I see, land is golden.

How will the stock market react to the upcoming election?

On one hand you've still got Bernanke promising to keep rates low. On the other hand, you've entered a new political world. The Republicans will want to show much more fiscal responsibility. And even if the Democrats are back, they will attempt to illustrate that they are also aware of the long-term problems of debt accumulation. My guess is that it's a tougher environment for the market starting next year.

Thursday, June 21, 2012

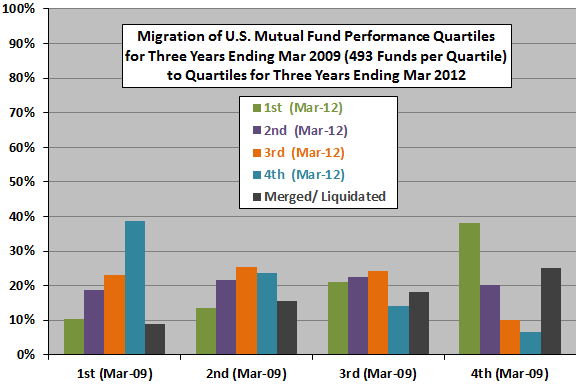

Mutual Fund Performance Persistence

Do top-performing mutual funds reliably continue to be top performers. In their June 2012 semiannual report entitled “Does Past Performance Matter? S&P Persistence Scorecard”, Standard and Poor’s summarizes performance persistence statistics for U.S. mutual funds overall and for funds grouped by capitalization focus of holdings. They measure persistence of the top 25% (quartile) and top half of funds across multiple subsequent years and frequency of migration of all performance quartiles from one multi-year interval to the next. Using annual performance data for a broad sample of U.S. mutual funds during March 2002 through March 2012, they find that:

- Only 4.05% (19.6%) of mutual funds in the top performance quartile (half) as of March 2010 persist in the top quartile (half) for both of the next two years, compared to 6.25% (25%) for random expectations.

- Only 0.93% (5.22%) of mutual funds in the top performance quartile (half) as of March 2008 persist in the top quartile (half) for all of the next four years, compared to 0.39% (6.25%) for random expectations.

- There is some tendency toward reversal of fortune of the best and worst funds across consecutive, non-overlapping three-year and five-year performance intervals (see the chart below).

- Results are generally consistent across groups of funds segmented by stock capitalization focus (size style).

In summary, evidence casts doubt on the existence of U.S. mutual fund manager skill and indicates that fund performance is more likely to reverse than persist.

Cautions regarding findings include:

- Since the report does not address factors related to performance persistence, findings do not obviously translate into a fund switching strategy.

- Performance measurements address size of holdings but not other factors commonly applied to alpha (book-to-market and momentum).

unconstrained

-

So-called “unconstrained” bond funds got very hot a while ago, so it’s time to check in on how they’ve done.

For background, you can read a couple of postings from April 2011. One from Josh Brown looked at the popularity of the vehicles at the time, while David Merkel examined them in a historical context and pointed out some important issues for investors. The remainder of the year included weak performance from most of them, the crux of a December piece from Bloomberg.

The three mutual funds shown above were featured in that Bloomberg story. They are JPMorgan Strategic Income Opportunities (JSOAX), PIMCO Unconstrained Bond (PUBAX), and Eaton Vance Global Macro Absolute Return (EAGMX). Pictured too is the iShares Barclays Aggregate Bond ETF (AGG), which has easily beaten all of them since the start of 2011. This longer chart begins in 2009.

Monday, June 18, 2012

Eric Sprott on the Recent Volatility in Gold

Seeing how gold has seen volatility as of late and numerous top hedge

funds hold physical gold, we thought it would be prudent to check in

with one of the most outspoken gold advocates: Eric Sprott of Sprott

Asset Management.

After all, gold is one of Dan Loeb's top holdings at Third Point. David Einhorn of Greenlight Capital has long held physical gold as a top stake. And we highlighted in April how John Burbank's Passport Capital had been buying gold.

So what do investors make of the latest volatility? Eric Sprott and Shree Kargutkar put out an interesting note on the precious metal on June 8th:

Sprott on Gold

"There have been key developments in the physical gold market over the last few weeks which we feel are worth highlighting:

1) The Chinese gold imports from Hong Kong in April, 2012 surged almost 1300% on a YoY basis. Total gross imports for the month of April were 103.6 tonnes and the net imports were 66.3 tonnes1. It is not the data for April alone which has caught our eye. There has been a stunning increase of gold imports through Hong Kong for export into China over the past 2 years. Between May 2010 and April 2011, China imported a net 66 tonnes of physical gold through Hong Kong. Between May 2011 and April 2012, that number jumped to 489 tonnes. This represents an increase of 640%.

2) Central banks from around the world bought over 70 tonnes of gold in April, 2012. Data from the IMF showed developing countries such as the Philippines, Turkey, Mexico and Sri Lanka were significant buyers of gold as prices dipped.

3) Iran purchased $1.2B worth of gold in April, 2012 through Turkey. As the developed nations continue devaluing their currency at the expense of developing nations, countries such as Iran, China and Mexico are forced to look at alternative stores of value.

4) After twenty years of lackluster returns and stagnant bond yields, Japanese pension funds have finally discovered the value of investing in gold. The $500M Okayama Metal and Machinery pension fund placed 1.5% of its assets into gold bullion-backed ETFs in April in order to "escape sovereign risk"4.

5) Bill Gross writes, "Soaring debt/GDP ratios in previously sacrosanct AAA countries have made low cost funding increasingly a function of central banks as opposed to private market investors. Both the lower quality and lower yields of previously sacrosanct debt therefore represent a potential breaking point in our now 40-year-old global monetary system. […] As they (investors) question the value of much of the $200 trillion which comprises our current system, they move marginally elsewhere — to real assets such as land, gold and tangible things, or to cash and a figurative mattress where at least their money is readily accessible". Is the bond king recommending gold? YES, YES YES!

6) The Gold Mining ETF, GDX, has seen strong inflows in the past 3 months. The number of units outstanding have increased from 162.5M to roughly 187M between March 1, 2012 and May 31, 2012. This represents an increase in assets of almost $1.2B in a span of 3 months. It is worth pointing out that for a majority of this three months period, GDX, and by extension the gold mining companies were experiencing significant declines in their market values.

We believe there has been a material change in the gold investing landscape. The HUI, which is the Gold Bugs Index, is now up over 20% from its lows since May 16th, 2012. The slide in gold equities seems to be subsiding as a foundation for a strong move upwards is set. New buyers, represented by the Chinese, central banks, Japanese pension funds and the Iranians, bought almost 140 tonnes of gold in April alone. To put this into perspective, the annual gold production is approximately 2600 tonnes. China and Russia produce around 500 tonnes of gold annually, which never makes it to the open market. This leaves about 2100 tonnes of gold production annually for the rest of the world.

When buyers representing 140 tonnes of new demand enter a market which only has 175 tonnes of monthly supply, we are left wondering about two things:

1) In a balanced market, where is the source of supply to the new buyers going to come from?

2) How can a new buyer of size get into the gold market, which is already balanced, without significantly impacting the price of gold? The answer is fairly obvious. When demand outstrips supply, prices move higher. These significant macro changes in the supplydemand dynamic of the gold market should propel the price of gold to new highs."

For more from this fund manager, we've also highlighted Sprott's previous commentary on how 2012 is the year of the central bank.

After all, gold is one of Dan Loeb's top holdings at Third Point. David Einhorn of Greenlight Capital has long held physical gold as a top stake. And we highlighted in April how John Burbank's Passport Capital had been buying gold.

So what do investors make of the latest volatility? Eric Sprott and Shree Kargutkar put out an interesting note on the precious metal on June 8th:

Sprott on Gold

"There have been key developments in the physical gold market over the last few weeks which we feel are worth highlighting:

1) The Chinese gold imports from Hong Kong in April, 2012 surged almost 1300% on a YoY basis. Total gross imports for the month of April were 103.6 tonnes and the net imports were 66.3 tonnes1. It is not the data for April alone which has caught our eye. There has been a stunning increase of gold imports through Hong Kong for export into China over the past 2 years. Between May 2010 and April 2011, China imported a net 66 tonnes of physical gold through Hong Kong. Between May 2011 and April 2012, that number jumped to 489 tonnes. This represents an increase of 640%.

2) Central banks from around the world bought over 70 tonnes of gold in April, 2012. Data from the IMF showed developing countries such as the Philippines, Turkey, Mexico and Sri Lanka were significant buyers of gold as prices dipped.

3) Iran purchased $1.2B worth of gold in April, 2012 through Turkey. As the developed nations continue devaluing their currency at the expense of developing nations, countries such as Iran, China and Mexico are forced to look at alternative stores of value.

4) After twenty years of lackluster returns and stagnant bond yields, Japanese pension funds have finally discovered the value of investing in gold. The $500M Okayama Metal and Machinery pension fund placed 1.5% of its assets into gold bullion-backed ETFs in April in order to "escape sovereign risk"4.

5) Bill Gross writes, "Soaring debt/GDP ratios in previously sacrosanct AAA countries have made low cost funding increasingly a function of central banks as opposed to private market investors. Both the lower quality and lower yields of previously sacrosanct debt therefore represent a potential breaking point in our now 40-year-old global monetary system. […] As they (investors) question the value of much of the $200 trillion which comprises our current system, they move marginally elsewhere — to real assets such as land, gold and tangible things, or to cash and a figurative mattress where at least their money is readily accessible". Is the bond king recommending gold? YES, YES YES!

6) The Gold Mining ETF, GDX, has seen strong inflows in the past 3 months. The number of units outstanding have increased from 162.5M to roughly 187M between March 1, 2012 and May 31, 2012. This represents an increase in assets of almost $1.2B in a span of 3 months. It is worth pointing out that for a majority of this three months period, GDX, and by extension the gold mining companies were experiencing significant declines in their market values.

We believe there has been a material change in the gold investing landscape. The HUI, which is the Gold Bugs Index, is now up over 20% from its lows since May 16th, 2012. The slide in gold equities seems to be subsiding as a foundation for a strong move upwards is set. New buyers, represented by the Chinese, central banks, Japanese pension funds and the Iranians, bought almost 140 tonnes of gold in April alone. To put this into perspective, the annual gold production is approximately 2600 tonnes. China and Russia produce around 500 tonnes of gold annually, which never makes it to the open market. This leaves about 2100 tonnes of gold production annually for the rest of the world.

When buyers representing 140 tonnes of new demand enter a market which only has 175 tonnes of monthly supply, we are left wondering about two things:

1) In a balanced market, where is the source of supply to the new buyers going to come from?

2) How can a new buyer of size get into the gold market, which is already balanced, without significantly impacting the price of gold? The answer is fairly obvious. When demand outstrips supply, prices move higher. These significant macro changes in the supplydemand dynamic of the gold market should propel the price of gold to new highs."

For more from this fund manager, we've also highlighted Sprott's previous commentary on how 2012 is the year of the central bank.

Monday, June 04, 2012

The Hunch, the Pounce and the Kill

BOAZ WEINSTEIN didn’t know it, but he had just hooked the London Whale.

It was last November, and Mr. Weinstein, a wunderkind of the New York hedge fund world, had spied something strange across the Atlantic. In an obscure corner of the financial markets, prices seemed out of whack. It didn’t make sense.

Mr. Weinstein pounced.

As the financial world now knows, what was out of whack was JPMorgan Chase & Company. One its traders, Bruno Iksil, the man later nicknamed the London Whale for his outsize trades, was about to blow a multibillion-dollar hole in the mighty House of Morgan.

But the resulting uproar, in Washington and on Wall Street, has largely obscured a simple truth of the marketplace. Yes, Morgan lost big — but, as Mitt Romney has pointed out, someone else won. And that someone or, rather, those someones, turn out to be Boaz Weinstein and a wolf pack of like-minded hedge fund managers.

In the London Whale, these traders saw a rich opportunity, and they seized it with both hands. That, after all, is the way hedge funds roll. His cool calculus has made Mr. Weinstein a very rich man: he is in talks to buy the Fifth Avenue co-op of a reclusive heiress, Huguette Clark, for $24 million.

It might seem remarkable that someone like Mr. Weinstein, a man virtually unknown outside of financial circles, could deal such a stinging blow to one of the world’s largest, most respected banks. Jamie Dimon, the chairman and chief executive of JPMorgan and a face of the banking establishment, is struggling to contain the damage from what he has called a “terrible, egregious mistake.” The loss — JPMorgan put it at $2 billion, but it may turn out to be $3 billion or more — has renewed calls for stronger financial regulation.

Given the secretive nature of the business, few on Wall Street, including Mr. Weinstein, were willing to speak publicly about how the hedge funds harpooned the London Whale. But interviews with more than a dozen hedge fund managers, investors and traders pull back the curtain on the ways of this band of traders, and on what really happened.

One thing is sure: Mr. Weinstein, 38, played a central role in this, one of the biggest trading blowups since the financial crisis of 2008. Mr. Iksil and his colleagues in the chief investment office at JPMorgan may have lighted the fire, but Mr. Weinstein and his cohorts fanned the flames. In the hedge fund game, a business in which ruthlessness is prized and money is the ultimate measure, Mr. Weinstein is what is known as a “monster” — an aggressive trader with a preternatural appetite for risk and a take-no-prisoners style. He is a chess master, as well as a high-roller on the velvet-topped tables of Las Vegas. He has been banned from the Bellagio for counting cards.

From offices on the 58th floor of the Chrysler Building in Midtown Manhattan, Mr. Weinstein runs a $5.5 billion hedge fund firm called Saba Capital Management. (“Saba” is Hebrew for “grandfatherly wisdom,” a nod to his Israeli roots.) It was there, last autumn, that he noticed an aberration in the market for credit derivatives. He knew from experience what it was like to lose a lot of money at a big bank. Before starting Saba, he was responsible for a team that lost nearly $2 billion, in the depths of the financial crisis, at Deutsche Bank. Others lost even more. Last November, however, he saw that a certain index seemed to be trading out of line with the market it was supposed to track. He and his team pored through reams of data, trying to make sense of it.

Finally, as Mr. Iksil, the London Whale, kept selling, Mr. Weinstein began buying.

At the time, traders in London had no real idea that JPMorgan was behind the trades that were skewing the market in credit derivatives. In fact, they weren’t even sure that it was a single bank or trader. But soon the City of London, Europe’s financial hub, was buzzing. Whoever the mysterious trader was, he or she kept selling derivatives intended to rise in value in the event that certain corporate bonds became riskier. The volume of trades was off the charts. Who could possibly sell so much? And, what if the trade reversed, as it inevitably would?

And so the battle lines were drawn. On one side was JPMorgan, the American banking giant that had weathered the financial crisis far better than so many of its peers. On the other were hedge fund managers, including Mr. Weinstein at Saba.

Such standoffs are not uncommon on Wall Street. An aggressive trader makes a wrongheaded bet, then doubles down to scare off competitors on the other side of the trade. Market rivals often get slapped down, unwilling to keep buying as the other side is selling, or vice versa. For traders with the backing of a major bank, like JPMorgan, the task is much easier.

But not always. Sometimes, the other side sits tight, then hits back in force. And it does so in numbers.

By January of this year, the trade against the London Whale was not going well for the hedge funds. The price of the index, as well as others, was still falling, and the losses were mounting for Mr. Weinstein and the others. But by February, it was clear that a single, big player was behind the selling. On trading desks in London and New York, everyone was talking.

It had to be JPMorgan.

BOAZ WEINSTEIN has always played the wild card in the markets. He grew up on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, in relatively modest surroundings, the son of an automobile insurance salesman and a translator, both regular watchers of “Wall Street Week.” As a student at Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan, he entered a contest to see who could pick the best stocks. He won — by selecting an assortment of the fastest-growing stocks he could find from newspaper charts. He studied philosophy at the University of Michigan — he was partial to Hume and Camus — but today favors behavioral finance, particularly the work of his friend Dan Ariely, a professor at Duke. Mr. Weinstein is married to Tali Farhadian Weinstein, a rising lawyer in the Justice Department.

Last February, at a conference organized by another hedge fund manager, his friend William A. Ackman, Mr. Weinstein was hailed as one of the savviest credit traders in the business.

The February conference was held, ironically, in JPMorgan’s offices on Madison Avenue. Workers at the bank milled about as Mr. Weinstein and others offered investment tips.

Dressed in a sharp blue suit, Mr. Weinstein stepped up to the microphone and opened with a joke that only a financial wonk would appreciate. He showed a slide comparing the cost of credit default swaps on various government debt to the percentage of young men in those countries who live with their parents. The slide titled “Mamma Mia!” suggested that, by that measure, Greece, Portugal and Italy were in trouble.

But what really got people’s attention was his second-to-last slide. It was his pick for the “best” investment idea of the moment. Mr. Weinstein recommended buying the Investment Grade Series 9 10-year Index CDS — the same index that Mr. Iksil was shorting.

The crowd, 300 or so investment professionals, began buzzing.

“Once he came out in that meeting and was so specific, others jumped in,” one hedge fund manager said.

But the London Whale was so big that, for months, the hedge funds betting against him simply got steamrolled. One of Mr. Weinstein’s funds at Saba was down 20 percent heading into May.

Then the tables began to turn, as news reports about Mr. Iksil, fed by the hedge funds, began to surface on both sides of the Atlantic. Suddenly, everyone was checking out the obscure index that Mr. Weinstein and others had seized upon.

By May, when fears over Europe’s debt crisis again came to the fore, the trade reversed. The London Whale was losing. And Mr. Weinstein began to make back all of his losses — and then some — in a matter of weeks.

Other hedge funds were also big winners. Blue Mountain Capital and BlueCrest Capital, both created by former JPMorgan traders, were among those winners. Lucidus Capital Partners, CQS and a fund called III came out ahead, too.

INSIDE the hedge fund world, some joked that Mr. Weinstein had been able to spot the London Whale because he himself had been a whale once, too.

Mr. Weinstein was a pioneer in complex credit derivatives, latching onto them early in his tenure at Deutsche Bank, before they became the financial weapons of mass destruction that worsened the financial crisis. He was a profit machine at the bank, notching earnings in 10 of his 11 years trading there. At 27, he became one of the youngest managing directors in the bank’s history. Before his book blew up, Mr. Weinstein was reportedly pulling down about $40 million a year. He exploited price discrepancies and piled leverage into his trades.

Then his team at Deutsche Bank lost $1.8 billion during the 2008 financial crisis. The trading losses ruined bonuses throughout the bank, and ruffled more than a few feathers.

He would later leave the bank and, along with 12 of his colleagues, set up Saba. Mr. Weinstein started it with $140 million — a pittance by hedge fund standards. In the intervening years, he has outperformed his peers and managed to vacuum up assets at a time when most growing hedge funds have been struggling to hold on to what they’ve got. He now controls more than $5.5 billion.

The similarities between Mr. Weinstein and Mr. Iksil still resonate in the market.

“It was one whale versus another whale,” one hedge fund manager said.

Those who have traded against Mr. Weinstein describe him as an aggressive trader who bets big and moves fast. He values a deal more than old-fashioned etiquette. Traders tell tales of losing money to him because of split-second price differences he picked up faster than they did. While that kind of behavior doesn’t win a lot of friends on Wall Street, these traders concede that Mr. Weinstein is too big and powerful to ignore.

At a lot of large hedge funds, the top dogs bark orders to underlings, but Mr. Weinstein is almost always the one doing the trading at Saba. He calls around to the banks daily. His confidence and willingness to take on risk, however, leave some worried that he’s never too far away from another Deutsche Bank trade — from, in essence, becoming the whale.

“If you hand me a list of the top-performing guys in the space, I’d expect to see his name on it,” said one bank executive who works closely with hedge funds. “If you hand me another list of hedge funds that might blow up, I’d expect his name to be on that, too.”

Others disagree, saying that Mr. Weinstein has a long record as a steady performer.

LIKE many hedge fund traders, Mr. Weinstein is comfortable with risky pursuits, particularly those that require spot calculations and a cool head. A gambling enthusiast, he has an affinity for blackjack and poker. In 2005, Mr. Weinstein won a Maserati by competing in poker in a tournament sponsored by a unit of Warren E. Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway. Mr. Weinstein still drives the car. He plays with celebrities like Matt Damon, too.

Not everyone is enthusiastic about Mr. Weinstein’s playing style. A few years back, on a trip to Vegas, he was banned from the opulent Bellagio casino for counting cards while playing blackjack.

Much has also been made of his prowess as a chess player. He earned the chess master designation at the age of 16, and has remained a lifelong fan, though he plays less these days. At a charity auction in 2010, he paid $10,500 to play alongside the chess legend Garry Kasparov and the young chess sensation Magnus Carlsen.

Mostly, he sneaks in quick games online, sometimes with Peter Thiel, a hedge fund manager and Silicon Valley star who was an early investor in Facebook.

Both chess and playing the markets require a mind that can see several steps ahead of the next man — a fact that has not been lost on Wall Street. Privately, Mr. Weinstein tells friends that while skill at chess is great to have, it’s hardly a requisite for being a good trader.

Whatever the case, chess helped him gain his first real shot on Wall Street. At 18, after failing to land a summer job at Goldman Sachs, Mr. Weinstein ran into a senior partner in the bathroom on his way out. The partner, David F. DeLucia, a chess expert, had played Mr. Weinstein numerous times, and quickly arranged more meetings for him.

Now Mr. Weinstein is practically a featured attraction on Wall Street. He attends galas and charity events, and is sought out to speak at big events. Pictures of him clasping a drink at last night’s party appear with regularity on business Web sites.

And, financially, the payoff has been enormous. Last year, he earned more than $90 million and, by some estimates, landed on the rich lists of the hedge fund industry. Such figures aside, he is described as someone who doesn’t flash his wealth. Before he won his Maserati, he didn’t own a car.

At another recent investor conference, Mr. Weinstein strolled among the crowd in Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center. Accompanying him was his mother, Giselle, with whom he watched “Wall Street Week” as a child.

While hedge fund managers, investors and analysts mingled over cocktails, Mr. Weinstein appeared buoyant. His trade against the London Whale was finally paying off, a vindication — and a profitable one — of his hunch months earlier. That same day, news reports said Mr. Iksil, the London Whale, would soon be leaving JPMorgan.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Lou Manheim's Helpful Links

Lunch is for wimps

It's not a question of enough, pal. It's a zero sum game, somebody wins, somebody loses. Money itself isn't lost or made, it's simply transferred from one perception to another.