It is one thing to read

intellectually dishonest drivel about the municipal bond market in the

mainstream media (which investors appear to be ignoring anyway),

but it is another thing entirely to see it promoted as research by the

Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Such is the case with this post on The Untold Story of Municipal Defaults on Liberty Street Economics.

The basic argument of the post is that there are significantly more

municipal defaults than are commonly cited because the default

statistics many people cite come from the rating agencies, and the

rating agencies only cite defaults that occur within the universe of

credits they rate. The post then mentions default studies published by

Moody’s and Standard and Poor’s, which note that of the over 50,000

“municipal” issuers they rate, there have been 71 and 47 defaults,

respectively, since the 1970s. The Fed researchers then contrast these

figures with a database that includes unrated debt, and “discover” that

there have been 2,521 defaults over the same time period.

This will obviously be very distressing news to anyone who gets their

market research from Seeking Alpha. But default statistics that include

unrated debt are not difficult to come by, and these data are widely

cited in research notes from investment banks and independent advisory

firms. (They are also regularly cited in Bloomberg and the Bond Buyer.)

The Fed did not come by its data for this post any differently than any

other market participant does. As I mentioned at the end of my post

on California bankruptcies (quoting JP Morgan research), there have

been 47 first-time monetary defaults totaling $889 million YTD (with

Stockton expected to default on $230 million of debt next month), of

which 58% is unrated. If you exclude insured bonds, the total amount is

$725 million across 42 issuers. If you exclude a handful of cases where

debt service payments were late due to administrative errors and

oversights, the total is $549 million across 33 issuers. This is for a

$3.7 trillion market. Of course, the folks at the Fed did not find it

necessary to include a detail as trivial as the par amount of defaulted

bonds (or recoveries or defaults due to administrative errors that were

rectified) in their post.

I think a lot of the problems that the uninitiated encounter in

trying to understand credit risk in the municipal bond market relate to

the facile distinction between general obligation and revenue pledges

rather than an emphasis on the differences between the actual borrowers

in the “municipal” bond market – by which we really mean the

“tax-exempt” bond market. Governments issue both general obligation and

revenue debt and they create a lot of special districts and independent

issuers that complicate analysis. But there is also revenue debt that

is issued on behalf of non-governmental entities that is not even

remotely similar in nature. The federal tax code allows states to issue a

limited number of tax-exempt bonds for private business use every year.

These bonds are issued on behalf of private (corporate) borrowers and

are repaid from private resources. There are also a host of bonds issued

on a tax-exempt basis on behalf of non-profit entities, like hospitals

and colleges (although you would probably be surprised by the types of

enterprises that count as charitable organizations under the federal tax

code these days). This is not government debt. It is often not even a

question of whether they serve an inessential or essential purpose

vis-à-vis a governmental entity, as the post suggested – they are simply

getting a government subsidy for economic development or other

purposes. Literally the only thing these bonds have in common with

government debt is their tax status, and yet they are lumped in with

“municipal” bonds for statistical purposes. This is where the vast

majority of defaults occur, and it is why aggregate default statistics

are mainly only useful for making fun of Meredith Whitney. Most of the

“idiosyncratic events” that cause defaults among specific sectors do, in

fact, have well-documented narratives (e.g., dirt bonds).

I also thought the remarks at the end about how the near-demise of

the bond insurance industry has only complicated matters for investors

were rather humorous … in a post about unrated bonds. Perhaps someone

should explain to the NY Fed what types of bonds are insurable?

It is frustrating reading posts such as this because I know that an

uninitiated person will not read it and think, “bonds that are issued

without ratings, generally for private and not public purposes,

generally not by an issuer with the authority to levy taxes, and

generally sold to institutional investors may involve credit risk.” They

will instead think, “wow, municipal bonds are really risky, look at all

of these defaults that the so-called experts have missed,” because

heaven knows investors lose millions of dollars silently. And of course,

the fuckwits in the mainstream media and on blogs will talk about this

report non-stop as a vindication of their own misguided commentary, even

though they can’t even name a single default besides Jefferson County

and tend to get default and bankruptcy confused anyway.

By and large, it is not difficult to identify where credit risk

exists in the municipal bond market. If bonds are being sold unrated,

and it is not because the issuer is a small and inactive borrower, and

if there is a large private participation element, you might want to do

some more digging. One might argue that investors need to be exposed to

this information because they may be holding such risky, unrated paper

through funds. If that worries you, there are investments out there

besides high-yield funds.

The Fed really ought to be embarrassed that it published something like this.

The richest one percent of this country owns half our country's wealth, five trillion dollars. One third of that comes from hard work, two thirds comes from inheritance, interest on interest accumulating to widows and idiot sons and what I do, stock and real estate speculation. It's bullshit. You got ninety percent of the American public out there with little or no net worth. I create nothing. I own.

Tuesday, August 28, 2012

Arnott: Emerging Markets Still Look Good

Rob Arnott’s Research Affiliates can now boast about $60 billion in assets that use “fundamental” indexes from his Newport Beach, Calif.-based company that screens stocks based on book value, cash flow, sales and dividends. One wonders if the future of indexing will feature Arnott more and more. When IndexUniverse.com Managing Editor Olly Ludwig sat down with Arnott in his office, they talked about his disagreement with indexing legend John Bogle, the state of the ETF industry and the allure of investing in relatively debt-free emerging markets countries.

Ludwig: When we talk about the pioneers of indexing, there are those who say that the baton must be passed at some point, and that perhaps you represent the next chapter. How do you respond to those views?

Arnott: Well, I have enormous respect for Jack. He is one of my heroes in this business. He is one of the pioneers. But as with so many pioneers, the ideas that spawned his and Vanguard’s meteoric success—that if you hold costs down, the customer gets more; and that since departures from the market are a zero-sum game, you should just hold the market—are very powerful ideas. But as with so many pioneers, he latches onto those ideas tenaciously and defends them fiercely. And so to him, Fundamental Indexing is active management in drag.

Ludwig: I was going to say you are in his cross hairs in some sense.

Arnott: He and I are friends. But this is one area of fierce disagreement. Another is ETFs.

Ludwig: Let’s start with the “active management in drag”—I love that formulation—then we’ll move on to ETFs.

Arnott: OK. Viewed from the perspective of classic cap-weighted indexation, Fundamental Indexing is active management. Any departure from cap weight is active management, viewed from that perspective. What a lot of people miss is that there's another perspective. Viewed from the vantage point of the macroeconomy, the cap-weighted market is making huge active bets. During the Internet boom, Cisco was 4 percent of the market, when it was 0.2 percent of the economy, and that’s a huge active bet. And so viewed from that perspective, Fundamental Indexing is studiously seeking to mirror the look and composition of the economy and using it as an anchor to contra-trade against the market’s constantly changing views, expectations, speculations, fads, bubbles and crashes.

That’s the elegance of Fundamental Indexing. Viewed from the vantage point of the macroeconomy, Fundamental Indexing does its best to be passive. And cap weight winds up loading up on growth companies, safe havens, weighting companies in proportion to their popularity.

Ludwig: So there's a whole lot of nuance here that we’re not getting from Jack Bogle? For example, I’m guessing you’ll concede the point that the line between active and passive management has blurred in the last two decades.

Arnott: It’s gotten blurrier and blurrier. And Fundamental Indexing has helped to make it even more blurry.

Ludwig: So you don’t dispute Bogle’s assertion that Fundamental Indexing is “active management in drag?”

Arnott: Actually, I don’t. I accept the notion that, from a cap-weight-centric world view, it is active management in drag. But I take it a step further, and I say: “That’s not the only world view.” From an economy-centric world view, Fundamental Indexing is passive and cap weight is active. It’s a little like looking at the world with one eye, or the other eye or with both.

Ludwig: Let’s talk about your disagreement with Bogle regarding ETFs. I've heard him rail against ETFs. Interestingly, Vanguard’s own data don’t substantiate his point of view that people trade ETFs too much. Maybe it holds true for other fund sponsors, but for Vanguard it doesn’t. Yet he asserts their people are using that intraday tradability of ETFs and misusing it and hurting themselves. Is that something with which you agree?

Arnott: I don’t disagree. I think you can turn intraday and hurt yourself badly. I view ETFs as exactly what they are—mutual funds that you can trade intraday. Now, Jack has likened ETFs to giving kerosene to an arsonist. To be sure, you can do yourself serious damage. ETFs are a tool. Dynamite is a tool. Would the world be better off without dynamite? No. Should ETFs have a warning label? Yes. Should people use them carefully? Yes. Can you hurt yourself badly if you misuse them? Yes.

Ludwig: Are you suggesting that that disclosure is insufficient?

Arnott: No. There is ample disclosure. I think we’re over-regulated. But be that as it may, you’ve got to recognize that when you're dealing with adults making decisions for themselves, they have the primary responsibility to make decisions that avoid hurting themselves. And do ETFs create a greater opportunity for doing so than conventional mutual funds? Ever so slightly, yes. But people want that ability to choose their entry and exit points.

Ludwig: In this active vs. passive debate, I have conversations all the time where I'm preaching the gospel of indexing—buy, hold and rebalance. But I’m continually astonished that people, by and large, cannot believe that the guy from Harvard Business School can't beat one of Bogle’s cap-weighted funds year after year. And here’s my question: Does it make it easier for you to make your case for Fundamental Indexing by leveraging its incremental move in the active direction in such a manner as to kind of set the hook a little bit more?

Arnott: People intuitively know, unless they have a Ph.D. in neoclassical finance theory, that the market doesn’t always get it right. And if the market doesn’t always get it right, what could make more sense than to contra-trade against the extreme bets? This idea has gained very little traction in university endowments. Usually there is a famous professor on the board who will say, “It can't be this easy.” But it’s made huge traction in retail and in jumbo public funds, where they're familiar with indexing. And they're very frustrated at where cap-weighted indexes have led them astray.

Ludwig: How do you respond to a generic, if not fully informed, objection to your strategies? I’m thinking of PowerShares, because they certainly seem very committed to what you're up to. But their funds are more expensive than Vanguard funds, for example.

Arnott: My response to that is pretty straightforward. Which is overpriced, 10 basis points for assuredly minus 10 basis points alpha, or 40 basis points for an alpha that, over long periods of time, appears to be about 2 percent of outperformance per year?

Ludwig: So that 2 percent number is still in sharp focus?

Arnott: What’s interesting is, no, it hasn’t achieved S&P 500 plus 2 percent. It’s achieved S&P plus 1.2 in an environment in which value underperformed growth by 1.5 percent a year. So, if value is underperforming by a pretty solid margin, and we’re adding value, imagine how we’ll do when we get back to a normal environment where value typically wins.

Ludwig: So, when someone says, “Rob, this is just value investing in disguise,” would you say, “Bring it on. That’s exactly what I want you to say”? Or is it more nuanced than that?

Arnott: Well, that would be part of it. The other part of it is, isn't it amazing that, with value underperforming by 1.5 percent a year, this has beat the market by 1.2 net of all costs? That’s cool.

So to those who say it’s expensive, I would say, “Expensive relative to what? Expensive relative to index funds that add no value, incur trading costs, incur fees and therefore surely deliver the index minus a little? Only if you care solely about price. Expensive relative to active managers who charge 1 percent or more, and, on average, who deliver S&P minus 1 or 2 percent? Boy, that’s an easy comparison. And, relative to alpha? No, it’s cheap.”

So I view the pricing as very reasonable. The other element here is more nuanced. If somebody has a good idea, should they garner some rewards for it? And if we’re collecting 3 or 4 or 5 basis points—a nickel or less for every $100 somebody puts into one of these funds—is that unfair? So there is a fairness issue, too.

Ludwig: I wanted to ask you about the ETF industry, per se. There is a perception that’s developing now that growth is starting to slow down. The launches are slowing down. We watch the filing traffic going into SEC rather closely, and it seems to be slowing. Would you comment a little bit on your perception of where the industry is in terms of overall development?

Arnott: The industry is maturing, by which I mean we’re moving away from the stage of throwing spaghetti on the wall and seeing what will stick. We’re in the stage where product ideas have to make business sense. And we’re seeing that across the board. Now that doesn’t mean the innovation slows. It means the innovation gets more focused, more concentrated. You can still throw spaghetti on the wall if you're far enough out of the mainstream, and you have a distribution partner who is willing to give truly out-of-mainstream ideas a new try.

But ultimately, that notion of, “We’re in an entrepreneurial startup business and profits don’t matter as long as there is visibility to profits three to five years out,” that’s changing. The margins in this business are tight. The fees are squeezed.

Ludwig: OK. Now, let’s turn to your broad thinking and the three “D’s,”—debt, deficit and demographics—that I’ve read from you and heard from Jason Hsu. What is your perception about where things stand in a macro sense right now?

Arnott: Well, you’ve got deficit and debt playing out as a slow-motion train wreck across the developed world, and that’s going to be causing severe challenges for the coming decade. You’ve got demography as a longer-term backdrop. In effect, my generation has made promises that our kids and grandkids can't possibly afford to honor. And we declare them to be sacred-trust promises that we made to ourselves, that we expect our kids and grandkids to honor.

Ludwig: And you're saying this is simply not a sacred trust, and at some point we have to face that?

Arnott: These are not sacred trusts; they're promises that we made to ourselves without consulting our kids and grandkids and without prefunding. And we can't afford it anyway. So those deals have to change. And what we’re seeing in Europe are two things: Firstly, a profound reluctance to embrace the notion that—to borrow from Clinton’s campaign—it’s the spending, stupid. You and I can't spend money that we don’t make, not for long. And a country can't spend money it doesn’t make, not for long.

And so the spending has to come down to match tax revenues. There's no room in Europe to raise taxes and expect it to deliver higher tax revenues. Hollande’s hike in the top tax rate in France is not going to deliver more revenues; it’s going to deliver less. And most economists—even reasonably left-leaning economists—would say, “It’ll deliver less revenues.”

Ludwig: Because?

Arnott: Because, to borrow from Milton Friedman, few things in the world are more mobile than the affluent and their money. And so, if you can't close deficits with higher taxes, you have to close them with lower spending. We’re seeing a profound reluctance to acknowledge that with aging baby boomers in Europe—who are older than here and aging faster. The promises made to those boomers, by themselves, can't be honored by their kids and grandkids. There aren't enough of them.

So this is a slow-motion train wreck. The way it plays out is very simple: Spending will match tax revenues at some point in the not-too-distant future, sometime in the next several years. What we’re seeing is the political back and forth to find the path of least resistance to get there.

Ludwig: Yes, they're still playing out. So, if you're an investor, given this drag, clearly on the developed world, it doesn’t mean everything comes to a halt.

Arnott: Of course it doesn’t mean everything comes to a halt.

Ludwig: There are still investment opportunities, even in the developed world?

Arnott: Yes.

Ludwig: So, what’s most prospective now?

Arnott: Emerging markets, for the most part, don’t have large deficits; for the most part don’t have large debt burdens. Not because they wouldn’t be willing to have large debts, but because the markets won't let them. The debt burden of the emerging economies is 10 percent of the world total. For the G5, it’s 70 percent. Both represent 40 percent of world GDP. So one has seven times the debt coverage ratio of the other. Which would you rather own?

Ludwig: It would appear to be emerging. What about China—that country isn't without its problems, right?

Arnott: Well, you can't buy their bonds, anyway. And when people talk about China and the risk of a hard landing, if you push them and ask, “What do you mean by a hard landing?” The answer is that their growth could be less than 5 percent. We should be so lucky as to have that hurdle.

Ludwig: Right. So emerging markets are still worthwhile? And both stocks and bonds?

Arnott: Right. But global diversification has powerful merits.

Saturday, August 25, 2012

Bonds Much Sharpe -r Than Buffett

Mebane Faber’s post Buffett’s Alpha points out Warren Buffett’s 0.76 Sharpe Ratio discussed in the similarly title paper Buffet’s Alpha. I of course immediately think about the 8th Wonder of the World – the US Bond Market, whose Sharpe Ratio has trounced Buffett’s for the last 30 years. What I like even better are all the tactical systems that employ US bonds in their backtests and make no adjustment for substantially different returns going forward. For those of you who do not know, bonds with absolute certainty cannot achieve >8% annualized returns with max drawdown < 5% for the next 30 years with a starting yield to worst at 1.86% (Barclays Agg 8/23/2012).

If anyone can show me where to get 8% annualized returns with max drawdown of 5% for the next 30 years, please let me know, and I will buy that with leverage and enjoy life. I’ll be happy to share my gains with whomever has the answer.

In addition to an unbelievable Sharpe Ratio, bonds have exhibited a low/negative correlation with stocks during stocks’ bear market, which is also historically very anomalous.

Just because I love horizon plots.

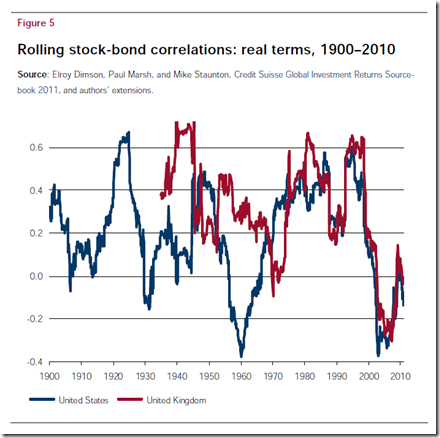

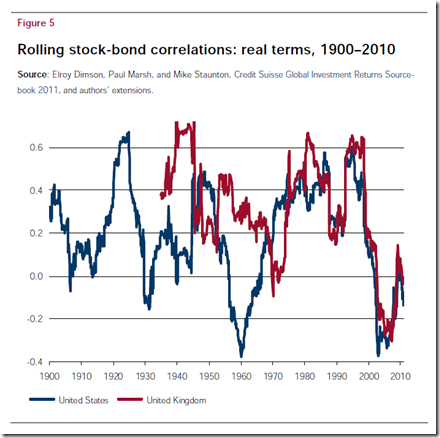

For a longer perspective, here is rolling correlation since 1900 from the CSFB 2011 Yearbook.

So the experience can be dramatically different than what we have been fortunate enough to experience recently.

If anyone can show me where to get 8% annualized returns with max drawdown of 5% for the next 30 years, please let me know, and I will buy that with leverage and enjoy life. I’ll be happy to share my gains with whomever has the answer.

|

| From TimelyPortfolio |

|

| From TimelyPortfolio |

|

| From TimelyPortfolio |

So the experience can be dramatically different than what we have been fortunate enough to experience recently.

Wednesday, August 22, 2012

With managed futures funds, think long think wrong

Short-term funds far outstripping those tracking longer trend lines; target 'overreactions'

Volatility generally spells trouble for managed-futures funds. But a number are poised to outperform if the market’s sleepy summer gets more exciting as the elections and fiscal cliff get closer.

Managed-futures funds, which invest in futures contracts, rely on momentum and trends to decide whether to be long or short a given commodity or asset class.

The market’s risk-on, risk-off roller coaster has wreaked havoc on that strategy. Last year, the average managed-futures fund was down nearly 7% and this year, the average is off another 2.5%, according to Morningstar Inc. A small group of managed-futures funds, however, has outperformed — thanks to a strict focus on only short-term trends.

“The managed-futures funds that are doing well are not your typical trend followers,” said Nadia Papagiannis, an alternatives analyst at Morningstar.

The MutualHedge Frontier Legends Fund Ticker:(MHFAX), which focuses on short-term trends, for example, had a 1.73% return in 2011, nearly 900 basis points better than the category average. The fund is up 2.3% year-to-date, nearly 500 basis points better than the average.

Perhaps most astonishing, those returns are net of the fund’s staggering 5.93% expense ratio. The higher expense ratio is a result of the fees charged by the commodity trade advisers with which the fund invests. The average managed-futures fund charges 2.67%, according to Morningstar.

Higher expenses tend to be the norm for the short-term funds, Ms. Papagiannis said. “They’re been more profitable, but they’re also more expensive,” she said.

Running counter to that assertion is the fact that the best-performing managed-futures fund of this year, the 361Managed Futures Strategy Fund Ticker:(AMFQX), has returned 8% year-to-date and has an expense ratio of 2.63%.

The fund, which was launched in November, follows a countertrend strategy that looks to buy oversold positions and short overbought positions, which it measures via an index’s 50-day moving average. The strategy is set up to take advantage of short-term swings; its average holding period is only about three days, said Brian Cunningham, president and chief investment officer of 361 Capital LLC, the fund’s adviser.

“What we’re looking for is short-term overreactions in the market, based on human emotion,” he said.

The fund is limited to investing in futures contracts on the S&P 500, Nasdaq and Russell 1000, which have liquid futures markets, to keep transaction costs minimal, Mr. Cunningham said.

Short-term trend-following strategies, not surprisingly, suffer the most when there is a long-term trend. In the first quarter of the year, as the S&P 500 marched upward, 361 Capital’s fund was down 90 basis points. Markets trending up or down favor longer-term-trend funds, said Ms. Papagiannis.

While beta, which is the non-correlated returns to stocks and bonds and is the one of the main appeals of managed-futures funds, historically has come from longer-term trend funds, the short-term trend funds have outperformed since they first came on the scene in 2011.

The fiscal cliff, the election, the ongoing troubles in Europe and China all point toward volatility continuing for the foreseeable future, however. That leads Ms. Papagiannis to believe the short-term managed-futures funds are likely to continue outperforming.

“In the near-term, the short-term trend followers are going to be more profitable,” she said.

The S&P Is At New Highs, Shanghai Is At New Lows — Jeff Gundlach Explains What's Going On

The Shanghai Composite is basically at post-crisis lows, while the S&P 500 is basically at post-crisis highs.

The S&P vs. the Shanghai Composite is a chart that fund manager Jeff Gundlach is fond of observing, so we asked him his take on what's going on.

He writes:

As a followup, we asked Gundlach if he thinks this divergence can last much longer

The S&P vs. the Shanghai Composite is a chart that fund manager Jeff Gundlach is fond of observing, so we asked him his take on what's going on.

He writes:

Strength is SPX and other "developed" stock markets reflects sentiment improvement regarding Europe versus the abject doom and gloom depths of late May/early June.

Weakness in SHCOMP reflects concern over slowing growth in China compounded by higher food and energy prices since late May/early June.

Since June 1 global "developed" stock market lows:

SPX price up 11.1%

SHCOMP price down 10.8%

IBEX price up 24.4%

The slow growth in China is much talked about, but the extra squeeze

from high food prices is probably a bit less appreciated. Rich countries

can handle a food price spike much more easily.Weakness in SHCOMP reflects concern over slowing growth in China compounded by higher food and energy prices since late May/early June.

Since June 1 global "developed" stock market lows:

SPX price up 11.1%

SHCOMP price down 10.8%

IBEX price up 24.4%

As a followup, we asked Gundlach if he thinks this divergence can last much longer

I doubt it. Thus short SPX long SHCOMP could be an interesting speculation. Probably a better trade today than the short SPX/long IBEX trade that has worked well since I recommended it at Ira Sohn (up 8.3% on the pair trade).

Copper Leads Global Growth

Market Notes

- Apple has become the world's largest company by market capitalisation... ever. It has now eclipsed Microsoft's market cap peak in late December 1999 during the technology bubble in nominal terms (not inflation adjusted terms). Amazingly, the parabolic run has created gains of 81 times over the last 10 years. Disclosure: I have started shorting Apple with OTM 2014 Puts.

- The Nasdaq Composite approached March highs on the back of some of the weakest and narrowest breadth I have ever seen. When we look at the number of tech stocks making 52 Week New Highs and smooth it out over an one month time frame, the results are flashing warning signals as majority of the tech companies are failing to confirm the rally.

- A few weeks ago I wrote about how the British Pound was a good short. I still believe this to be the case, as I think the Pound's major consolidation pattern will resolve to the downside. I believe that the UK is going to enter a more serious slowdown but I seem to be in the minority, as many traders turn very optimistic towards future prospects of the British Pound.

- Precious Metals are breaking out from their technical pressure points. We saw Platinum start the move, followed by Silver and finally Gold has now joined the party too. While gold bugs are celebrating, I think the real test is ahead of us. PMs need to prove that they can rally even if volatility rises, risk assets including stocks sell off and the US Dollar starts to rally again.

Big Picture

We continue to see that industrial economic barometers like Copper and

Crude Oil are failing to rise above the 200 day MA and confirm the

S&P 500's new highs in 2012. The Emerging Markets, saviour of

global growth in the post Lehman recovery, also continue to lag other

equity indices indicating that not all is well with the BRICs.

Furthermore, the short term rise in the DAX 30, Commodity Currencies and

Brent Crude (not shown here) has been almost vertical and caution is

advised. Finally, Gold seems to be attempting a technical upside

breakout, but the real test will be coming as global risk asset's

volatility rises and the US Dollar starts to rally again.

Leading Indicators

Global economic data continues to beat economist's expectations. Like

previously stated, this is a positive for the time being and it has been

helping global stocks and other risk assets move higher in the last

couple of weeks. However, keep in mind that this indicator does not

actually state weather or not global economy is improving, but just

weather the data is coming in below or above economists expectations.

During the middle of 2008, US economic data improved relative to

economists expectations, and yet the recession just intensified and

markets crashed afterwards.

Bulls from CNBC to Bloomberg are trying to convince bearish investors

that the US economy is improving. Even some of the more respected

investors are falling into the bullish trap as well. Some of them are

even celebrating the fact that the ECRI Growth Index has risen from

-3.5% to -0.6% (chart below) over recent weeks. Can I just ask, since

when did a negative leading economic number deserve so much celebration

and bullish speculation?

Do not believe the hype, as there is no strong evidence to support

economic improvements. Money printing is having less and less of an

effect on the economy. The chart above shows that every one of the

intermediate tops over the current secular bear market came during a

negative divergence between falling leading economic indicators and

rising equity prices. We currently have higher rising prices during

falling leading economic activity (another bearish non-confirmation), so

will this time be different?

The chart above, thanks to alsosprachanalyst.com, shows that Chinese

electricity output remains flat at best. Chinese National Bureau of

Statistics showed that hydroelectric power was the only reason that

overall output growth remained above 0%. More importantly, thermal power

output growth keeps sliding in July towards -4.5%. Why is this

important, you ask? Because electricity production has high correlation

with Chinese GDP (which cannot be completely trusted) and global mining

sector performance. All in all, Chinese leading data continues to slow.

China holds the key to future prospects of Copper prices, and the

feature article below explains why.

Featured Article

"China, the primary fundamental driver of the global copper price, has reported record-high semi-manufactured production rates, and a corresponding large drawdown in inventories. Now short copper, China’s likely to buy throughout H2, supporting the metal’s price."So UBS is bullish on Copper, one of the main barometers of global growth. I am in no position to argue for or against USB, as they have large team studying ground conditions regarding various Copper fundamentals, as well as in-house expert technical analysts. Nevertheless, I thought I would investigate matters further, but before we begin, it is important to understand that even though we are in a secular commodity bull market, there are periods when bears take over cyclical fundamental forces against the overall bullish price trend. One could say that we have been in a cyclical bear market for commodities for about a year now (chart below).

Personally, I follow Copper prices very closely and the reasoning is mainly towards its ability to predict global economic activity. I do not own any Copper, nor do I own any Copper mining companies. As we can see in the chart above, Copper prices have a close relationship with OECD Global Leading Economic Indicators. Therefore, one could easily understand that the peak in Copper prices, which occurred in February 2011, corresponded with the peak in global economic growth. The Global economy has been slowing since than, just as Copper prices have been in a downtrend (bear market).

Now, I am sure all the investors want to know if the bear market over?

Well to answer that question, one has to start paying closer attention to economic activity in Asia. This is most important for US-centric investors, who tend to hold a narrow minded vision towards the US and Europe (old world economy). You see, while the majority of investors are constantly focused on Europe and discussing Greece or Spain, it is China together with the rest of Asia that holds major upside as well as major downside risks to both the price of Copper and therefore the overall global economic activity.

The overall region consumes over 60% of the global Copper supply (including Japan), as we can see from the chart above thanks to UBS. It becomes plainly obvious that inter-linked growth spreads even further towards many commodity exporting countries like Brazil, Australia, Canada, Indonesia, South Africa, New Zealand, Argentina, Mongolia among many others. In other words if China, as well as overall Asia slow down, world growth will be heavily affected.

One region that is not affected yet is the United States. One important observation to make is that while Copper has been weakening since February 2011, which most likely tells us that Asia is slowing down meaningfully, the S&P 500 has continued to flirt with new highs in 2012. Therefore, bulls have started using the de-coupling phrase for the first time since late 2007. The UBS team of researchers also does not see any major problems ahead:

- "We forecast global copper demand growth of 3.2% to 20.6mt in 2012, driven by +6% in China (8.1mt), with only +0.4% in the G7 (5.3mt).

- China’s record-high semis production rate has resulted in a sharp drawdown in metal. As such, we should expect some price-supporting buying in H2.

- Policy easing in China, aimed at promoting economic activity, would also be price supportive events for the credit-driven trade of copper.

- UBS forecasts a deficit of 167kt in 2012 and market should then return to equilibrium in 2013E.

From the supply side perspective, I tend to agree with UBS that "a genuine supply response" is underway due to "prolonged strength in the copper price", as we can see with the chart above. Copper prices have been trading in a whole new range averaging about $4.00 per pound on the upside and $2.50 per pound on the downside. Having said that, I am much more concerned about the demand side, as I do not believe all is well with the Chinese economy, as already written about in the last post. It is difficult to judge the current true growth in the Chinese economy with official data saying 7.6%, while some well respected analysts say it is closer to 4%.

- Note: A genuine supply response to the prolonged strength in the copper price is underway, mainly out of South America."

With that in mind, I rather give the market a chance to tell me what is happening, while I sit back watch and listen. The chart above explains perfectly what I mean. We can see that the price of Copper has essentially gone nowhere over the last year or so, and we have now triangulated into the climax of a decision point.

A proper break out (no reversals) would establish a bullish foundation in a sign that the Chinese economy, together with rest of Asia, is not crashing with demand remaining strong. Global economic activity would therefore pick up across the globe and Copper prices would rise into new highs. This would stimulate the global mining sector, which is currently experiencing a severe downturn.

On the other hand, a break down would most likely signal that Asia as

well as China is in trouble, and that the Chinese property sector is

entering a hard landing scenario. Demand would be overwhelmed by supply,

which is still coming onboard and prices could fall hard in a

continuation of a cyclical downturn. The chart above shows that inverse

price of Copper correlates very well with the VIX, which currently finds

itself at very complacent levels, which in my opinion is a major warning signal.

Sentiment on Copper is slightly negative, but not extremely depressed.

The Daily Sentiment Index shows 30% bulls as of yesterday. Do keep in

mind that bulls dropped below 10% during September of 2008, only to see

Copper prices continue to crash in late 2008. Those who jumped in as

brave contrarians, dismissing selling pressure during the awful

fundamental backdrop, lost their shirt and their socks. Therefore, one

needs to understand that demand and supply fundamentals can overwhelm

the technical picture at times. One also needs to understand that

further price disappointments do occur from negative sentiment levels,

especially when there is failure to recover on the back of "stimulus

rumours".

For example, in the chart above we can see that hedge funds have been shorting Copper for weeks, which tends to be a contrarian buy signal and yet Copper prices have failed to stage a proper recovery from June lows. Compare that to the likes of US or German equities (Nasdaq or DAX) which seem to be rising vertically, and you can safely assume not all is well within the Copper market.

In summary, one can conclude that Copper is now at decision point and its technical break in either direction could tell us more about the future direction of the global economic activity than any analyst on CNBC or Bloomberg. Therefore, make sure you keep your eyes on the price of Copper over the coming weeks and months. As for my own view - I'm bearish and expect Copper to eventually break down before we bottom.

Trading Diary (Last update 22nd of August 12)

- Outlook: I am of the opinion that the risk asset bear market is upon us and that the global economy continues to slow rapidly into a recession. United States GDP has grown 5 out of the last 6 quarters below 2%, which tends to be stall speed. German GDP is also at stall speed, similar to 2008. China and India are slowing meaningfully and could experience a serious hard landing. At the same time US corporate earnings and gross profit margins are at record highs, so I expect a mean reversion unlike so many stock analysts. Cash levels with mutual funds, retail investors and money market funds are at extreme lows, financial stress is starting to rise, volatility is at very complacent levels and credit spreads are very narrow relative to fundamentals, so I expect a risk off scenario in due time.

- Long Positioning: Long focus is towards secular commodity bull market, with Precious Metals and Agriculture offering the best value. Largest commodity position is held in Silver, as central banks will eventually print money as the global economic activity deteriorates. Since Silver has broken out recently, hedges have been removed and a small purchase was made. Any negative reversal, as global risk asset volatility rises, will call for hedging again. NAV long exposure is about 100%.

- Short Positioning: Short focus is towards secular equity bear market, with cyclical sectors and credit offering best selling opportunities due to deteriorating global growth. Mild to modest exposure is held short in the Junk Bond market, as well as various economically sensitive cyclical sectors like Technology, Discretionary and Dow Transportation. Recently, the Apple parabolic has been shorted with long dated 2014 OTM puts. NAV short exposure is about 60%.

- Watch-list: Commodity currencies like Aussie, Kiwi and Loonie are also on my watch list of potential shorts right now, as negative surprises await with China slowing dangerously. With Euro being the most hated currency, a better risk off trade could be selling the British Pound. A major short in due time will be US Treasury long bonds, as they are extremely overbought and in a mist of a huge bubble mania, but first we have to wait for the Eurozone dust to settle. Finally, while Grains have exploded up, Softs still present amazing value for long term investors, with Sugar being my second favourite commodity (after Silver).

What I Am Watching

Back in the Economic Danger Zone

In its State Coincident Indexes report, the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

publishes gauges, calculated from four state-level indicators, that

summarize current economic conditions in each of the 50 states.

The Philly Fed also produce one- and three-month diffusion indexes derived from aggregate changes in the state-level indexes that offer a read on what is happening in the U.S. economy as a whole.

If the history of the past three decades or so is any guide, the latest data indicates, contrary to what the experts keep telling us, that we are in or entering an economic downturn.

The Philly Fed also produce one- and three-month diffusion indexes derived from aggregate changes in the state-level indexes that offer a read on what is happening in the U.S. economy as a whole.

If the history of the past three decades or so is any guide, the latest data indicates, contrary to what the experts keep telling us, that we are in or entering an economic downturn.

Cautious investors may tame hedge funds, at a cost

* Institutions push hedge funds to curb risk-taking

* Many want funds to cut leverage, protect against losses

* Some steer clear of short-selling

An academics' pension fund, the Church of Sweden and a biomedical charity are among conservative investors breaking with tradition and piling into hedge funds who are willing to curb their highest-risk bets to attract their cash.

Five years into the financial crisis, volatile markets and rock-bottom interest rates have crushed the returns of charities and pension funds, making it harder to meet their liabilities in paying for their members' retirements.

So many are now pinning their hopes on hedge funds to preserve, as well as grow, their money.

"We invest in hedge funds to diversify and reduce risks, we are not looking for them to shoot the lights out," Mike Taylor, chief executive of the London Pensions Fund Authority (LPFA), said.

Institutional investors like the LPFA, which runs 4.2 billion pounds ($6.6 billion) for state workers in the UK's capital, now account for two-thirds of hedge fund assets compared with less than a fifth in 2003, according to Deutsche Bank estimates.

Many funds are willing to adapt their higher-risk trading strategies to suit these more cautious institutions, because they usually invest for longer than the high-rolling wealthy individuals who once provided the bulk of their firepower.

But in demanding downside protection from their new funds, instead of high-risk strategies that can produce big returns - or similarly large losses - the investors could end up disappointed with how the hedge fund of the future performs.

LESS RISK, LOW LEVERAGE

The shift in the investor base has already influenced the popularity of different hedge fund strategies.

The reputation of the long-short equity fund, one of the most commonly used hedging strategies which rests on betting on some stocks to fall as well as some to rise, plunged after many managers failed to shield investors from stock market losses, boosting the appeal of rival strategies viewed as less volatile.

A category known as CTA (for commodity trading advisors ) for instance, which are computer-driven funds designed to latch on to trends in futures markets, has almost doubled in size between 2008 and the end of 2011 to $188 billion, according to industry tracker Hedge Fund Research.

Some, such as Michael Powell, head of alternatives at Britain's 32 billion pound Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS), argue the returns from such strategies are more dependable than a one-way bet on the stock market.

" For USS , hedge funds are less risky than equities. The volatility of our hedge fund programme is less than a third of that of public equities," Powell said.

Other investors place outright bans on investing in those they deem too daredevil.

The Wellcome Trust, a London-based charity which funds biomedical research and had almost 2.5 billion pounds invested across 38 different hedge funds last year, avoids those which use substantial debt or leverage to magnify their return on equity.

Hedge funds keen to reel in these more mainstream backers appear to have got the message.

Fund leverage has barely budged despite growth in the industry i n recent years and remains around 3.5 times net asset value, reflecting a drop both in demand to borrow and bank appetite to lend, the Financial Services Authority said in a paper published earlier this year.

Managers might also be tempted to scale back bolder bets because they are aware that their new investor base is less tolerant of high risk-taking, says Damien Loveday, global head of hedge fund research at consultancy Towers Watson.

SHORT-SELLING

As well as demands to mitigate risk, the more ethically-minded investors even go as far as to stay clear of funds which engage in certain activities, such as speculating on falling share prices or betting on the rising cost of food staples like corn, rice and wheat.

Robert Howie, a research director at Mercer, which advises investors on their hedge fund investments, told Reuters some pension funds require managers to carve out parts of their strategies into separate accounts.

The Church of Sweden for example invests in fixed income-focused managers but tends to avoid equity hedge funds, because of short-selling concerns and the high turnover of positions which clashes with its long-term investment approach.

The Church of England's 1.1 billion pound pension fund, which has invested in funds run by Winton Capital, Bridgewater and BlackRock, screens managers according to strict ethical criteria, such as excluding investments in firms involved in gambling, pornography and military products.

Cutting risk and keeping more of their assets in cash has helped hedge funds avoid some of the big falls seen in bonds and equities, but it has also meant many lag when markets recover.

The average hedge fund was up 1.87 percent for the first six months of 2012, Hedge Fund Research shows, below a 7.6 percent gain in the MSCI World Index, a measure of world equity prices.

"One of the attractions of hedge funds is their flexibility; their ability to short-sell and use leverage where appropriate," Mercer's Howie said. "To some extent, those investors are shooting themselves in the foot."

Friday, August 17, 2012

The Muni-Bond Technical Tango

Municipal bankruptcies are hitting the headlines again, and much of the recent action is coming out of the Golden State. Stockton, Calif., filed for Chapter 9 bankruptcy protection on June 29, becoming the largest city and third largest municipality to declare bankruptcy. Small ski town Mammoth Lakes followed a week later, and the city of San Bernardino voted to file shortly after that.

A muni-market bankruptcy trifecta is a rare thing, and this news would have caused plenty of hand-wringing in late 2010, when bonds were selling off and default paranoia reached a fever pitch. But muni investors are shrugging it off this time around. In fact, they've gotten more comfortable with risk as the year has progressed, even as muni-bond yields have continued to grind lower. High-yield muni funds in particular have been in vogue lately, taking in nearly $4 billion during the past three months alone.

It's not hard to see what's driving investor interest. The Federal Reserve's actions since the financial crisis--the zero interest-rate policy, quantitative easing, and Operation Twist--seem designed to push returns-starved investors into riskier assets by keeping yields on "risk-free" U.S. Treasuries and other high-quality assets repressively low. That trend has played out elsewhere in the bond market, too: Both high-yield corporate and emerging-markets bond funds have taken in roughly $45 billion combined over the past 12 months. Reinforcing this behavior, risk-taking has paid off for muni investors lately. The typical high-yield muni fund has already gained close to 10% for the year to date through July 31. The median national long-term muni fund, the next-best-performing muni category, is more than 3 percentage points behind.

Strong Demand Meets Scant Supply

Even though muni funds have maintained a blistering pace lately, a reversal isn't necessarily imminent, and the muni market's unique technical dynamics partly explain why. Individual investors' hunt for yield remains a key driver of flows into muni funds, for instance. When bond yields are falling, muni investors often buy funds instead of individual bonds. That's because funds, due to their mix of older bonds with higher payouts, tend to offer more attractive income streams than what an investor could buy in the market directly. As muni yields have plunged over the past year, refunding activity--issuers replacing higher coupon bonds nearing their call dates by issuing new bonds--has picked up, leaving individuals with cash to reinvest in a climate of painfully low yields. As long as that trend persists, it could support ongoing inflows to muni funds.

But whether individuals are buying funds or purchasing bonds directly, their appetite holds particular sway in the muni market compared with taxable-bond markets. Households own half of the outstanding $3.7 trillion muni market directly and mutual funds own another 22%, according to the Federal Reserve's December 2011 Flow of Funds report.

Muted supply is another factor working in the market's favor. Although gross muni issuance has picked up from 2011's low, roughly two thirds of new supply is coming from refundings, according to some estimates, a larger portion than usual. This has contributed to negative net new issuance--meaning total redemptions from refundings and maturities have outpaced total new supply--resulting in fewer bonds available to meet demand, a condition which some analysts expect to continue in coming months. BlackRock's muni-bond group head Peter Hayes also suggests that a broader deleveraging trend among municipalities could cause the total amount of municipal bonds outstanding to decline over the next five years, as the political climate favors frugality over more spending.

What Could Go Wrong?

But have these technical dynamics made muni-fund investors too complacent? On one hand, it's understandable that investors aren't panicking over a few bad headlines this time around. Fidelity muni head Jamie Pagliocco noted that the latest wave of California bankruptcies hasn't disrupted the market partly because the size of the debt outstanding isn't too concerning. According to JPMorgan, the total debt of these three issuers adds up to just 0.15% of the California muni market and 0.03% of the national market.

Muni investors hate surprises, though, and bad news could still be a potential source of volatility. With muni yields at all-time lows, it may not take much of a shock to shake things up. For example, the broadly diversified

In addition to a resurgence of headline risk, factors such as rating agency downgrades or an unexpected spike in new issuance could rattle the market. Don't underestimate the ability of a plain-old interest-rate bear market to test muni investors' resolve, either. Looking back at late 2010's sell-off and mass exodus from muni funds, most tend to pin the blame on Meredith Whitney's Dec. 19, 2010, appearance on "60 Minutes." But by the time Whitney made her doomsday prediction, muni prices were already falling and investors had started to pull their money out of muni funds. The shift occurred in November 2010, around the time U.S. Treasury yields also sold off sharply following the Federal Reserve's announcement of a second round of quantitative easing. Even a temporary spike in Treasury yields in the year ahead could snap muni investors out of their sanguine mood.

Recent fund flows could also be a contrarian indicator. After all, muni-fund investors' timing hasn't been great lately. In January 2011, investors pulled an estimated $12 billion out of muni funds when yields were at elevated levels. Going back to the Vanguard fund example, flows didn't turn modestly positive for until September of last year, but by that time, returning investors would have already missed out on two thirds of the year's gains. So far in 2012, investors have continued to sock another $34 billion into open-end muni funds after they've already had a heady run. Those jumping on the high-yield muni bandwagon in recent months especially have already missed out on a substantial amount of price appreciation.

As long as yields remain low or continue to grind lower, investors may be tempted to take on even more credit or interest-rate risk in order to squeeze every last drop of income out of a bone-dry market. Plus, the longer the muni market rewards risk-taking, the more likely that riskier funds' records will start to tempt investors. For example, 2008's historic downturn has already rolled off funds' trailing three-year records but still include much of 2009's rally, penalizing the more conservatively run offerings out there. Investors enticed by these records and relatively plump payouts will leave themselves vulnerable should the market turn. In a market that's priced to perfection, a muni-fund investor's best defense is a good memory.

Wednesday, August 15, 2012

The Untold Story of Municipal Bond Defaults

The last couple

of years have witnessed threatened or actual defaults in a diversity of

places, ranging from Jefferson County, Alabama, to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, to Stockton, California.

But do these events point to a wave of future defaults by municipal

borrowers? History—at least the history that most of us know—would seem

to say no. But the municipal bond market is complex and defaults happen

much more frequently than most casual observers are aware. This post

describes the market and its risks.

The $3.7 trillion U.S. municipal bond market is perhaps best known

for its federal tax exemption on individuals and its low default rate

relative to other fixed-income securities. These two features have

resulted in household investors dominating the ranks of municipal bond

holders. As shown below, individuals directly hold more than half, or

$1.879 billion, of U.S. municipal debt; when $930 billion in mutual fund

holdings is included, the household share rises to three-quarters.

Although the low default history of municipal bonds has played a key

role in luring investors to the market, frequently cited default rates

published by the rating agencies do not tell the whole story about

municipal bond defaults.

Two large bond rating agencies, Moody’s Investors Service (Moody’s) and Standard and Poor’s (S&P) provide annual default statistics for the municipal bonds that they rate. S&P reports that its rated municipal bonds defaulted only 47 times from 1986 to 2011. Similarly, Moody’s indicates that its rated municipal bonds defaulted only 71 times from 1970 to 2011. As shown in the table below, this record of defaults compares very favorably with the corporate bond market, especially given the larger number of issuers in the municipal bond market.

However, not all municipal bonds are rated and the market’s rated universe only tells part of the story. We have developed a more comprehensive municipal default database by merging the default listings of three rating agencies (S&P, Moody’s, and Fitch) with unrated default listings as tracked by Mergent and S&P Capital IQ. Rather than confirming Moody’s 71 listed defaults from 1970 to 2011, our database shows 2,521 defaults during this same period. Similarly, our database indicates 2,366 defaults from 1986 to 2011 versus S&P’s 47 defaults during this same period. In total, we find 2,527 defaults from the period beginning in the late 1950s through 2011. (We don’t have complete information on the number of issues, so we can’t compare default rates.)

Our findings raise the question, What causes such markedly different default frequencies between rated and unrated municipal bonds? Our answer: Not all municipal bonds are created equal. Different types of municipal bonds are secured by very different revenue sources with varying levels of predictability and stability. Furthermore, we believe that rated municipal bonds tend to be self-selected: issuers are less likely to seek ratings if their municipal bonds are not likely to achieve investment grade ratings.

To provide some background, we note that the municipal market is bifurcated into general obligation (GO) bonds and revenue bonds. GO bonds carry the broad full faith and credit pledge of a state or local government.; GO pledges are considered among the strongest type of security because municipalities have the authority to levy taxes; GO defaults like those in Jefferson County and Harrisburg are relatively rare. Revenue bonds, on the other hand, are backed only by a pledge of revenues raised from a specific enterprise, such as an airport, toll road, hospital, or school. GO bonds are therefore stronger than revenue bonds, because the revenue base for general obligations is much broader (for example, the ability to levy taxes on property or citizens within a specific geographic area) than the typical revenue bond revenue base (for example, a specified stream of revenue or enterprise).

The default risk of a revenue bond varies with the essentiality of the service provided by the enterprise. For example, water and sewer utilities provide essential services and thus have a strong ability to generate revenue. By contrast, the services offered by an alternative energy plant, pollution control facility, or other corporate-like entity may not be considered essential, because of the availability of other energy sources. Thus, these enterprises may have less potential to generate revenue. Alternative energy plants, pollution control facilities, and other corporate-like enterprises are all examples of industrial development bonds (IDBs). IDB financing projects using new technologies or projects with no historical track record tend to make up a majority of unrated IDB defaults.

It is also not surprising that revenue bond sectors, such as IDBs, experienced more defaults than GO bonds because they have made up almost two-thirds of municipal new issuance since the mid-1990s. While total municipal issuance has bounced around over the past sixteen years, revenue bonds have remained between 60 percent and 70 percent of new issuance.

To clarify how the number and behavior of municipal bond defaults compare with those of corporate bond defaults, the graphs below plot each series against the Philadelphia Fed’s national coincident index, a proxy for GDP. In the case of corporate bonds, defaults occur at a higher frequency during recessionary periods. In contrast, the pattern of municipal bond defaults appears less tied to recessionary periods. The absence of a clear pattern leads us to believe that municipal bond defaults may be more a function of idiosyncratic factors associated with individual sectors or issues than the result of broad macroeconomic developments.

The second graph also illustrates one of the main points of our post: the untold story of municipal bonds is that default frequencies are far greater than reported by the major rating agencies. Again, this is partly because the rating agencies’ default numbers only cover bonds that they rate, and the unrated portion of the market can be home to municipal bonds of lower credit quality, exhibiting a higher frequency of defaults. Until recently, investors could take some comfort from the fact that many municipal bonds—both rated and unrated—carried insurance that paid investors in the event of a default. But now that bond insurers have lost their AAA ratings, they no longer play a significant role in the municipal bond market, increasing the risks associated with certain classes and certain issuers of municipal debt.

In a coming post, we will explore a municipal bond sector—industrial development bonds—where defaults have been relatively common, highlighting specific examples of defaults.

Two large bond rating agencies, Moody’s Investors Service (Moody’s) and Standard and Poor’s (S&P) provide annual default statistics for the municipal bonds that they rate. S&P reports that its rated municipal bonds defaulted only 47 times from 1986 to 2011. Similarly, Moody’s indicates that its rated municipal bonds defaulted only 71 times from 1970 to 2011. As shown in the table below, this record of defaults compares very favorably with the corporate bond market, especially given the larger number of issuers in the municipal bond market.

However, not all municipal bonds are rated and the market’s rated universe only tells part of the story. We have developed a more comprehensive municipal default database by merging the default listings of three rating agencies (S&P, Moody’s, and Fitch) with unrated default listings as tracked by Mergent and S&P Capital IQ. Rather than confirming Moody’s 71 listed defaults from 1970 to 2011, our database shows 2,521 defaults during this same period. Similarly, our database indicates 2,366 defaults from 1986 to 2011 versus S&P’s 47 defaults during this same period. In total, we find 2,527 defaults from the period beginning in the late 1950s through 2011. (We don’t have complete information on the number of issues, so we can’t compare default rates.)

Our findings raise the question, What causes such markedly different default frequencies between rated and unrated municipal bonds? Our answer: Not all municipal bonds are created equal. Different types of municipal bonds are secured by very different revenue sources with varying levels of predictability and stability. Furthermore, we believe that rated municipal bonds tend to be self-selected: issuers are less likely to seek ratings if their municipal bonds are not likely to achieve investment grade ratings.

To provide some background, we note that the municipal market is bifurcated into general obligation (GO) bonds and revenue bonds. GO bonds carry the broad full faith and credit pledge of a state or local government.; GO pledges are considered among the strongest type of security because municipalities have the authority to levy taxes; GO defaults like those in Jefferson County and Harrisburg are relatively rare. Revenue bonds, on the other hand, are backed only by a pledge of revenues raised from a specific enterprise, such as an airport, toll road, hospital, or school. GO bonds are therefore stronger than revenue bonds, because the revenue base for general obligations is much broader (for example, the ability to levy taxes on property or citizens within a specific geographic area) than the typical revenue bond revenue base (for example, a specified stream of revenue or enterprise).

The default risk of a revenue bond varies with the essentiality of the service provided by the enterprise. For example, water and sewer utilities provide essential services and thus have a strong ability to generate revenue. By contrast, the services offered by an alternative energy plant, pollution control facility, or other corporate-like entity may not be considered essential, because of the availability of other energy sources. Thus, these enterprises may have less potential to generate revenue. Alternative energy plants, pollution control facilities, and other corporate-like enterprises are all examples of industrial development bonds (IDBs). IDB financing projects using new technologies or projects with no historical track record tend to make up a majority of unrated IDB defaults.

It is also not surprising that revenue bond sectors, such as IDBs, experienced more defaults than GO bonds because they have made up almost two-thirds of municipal new issuance since the mid-1990s. While total municipal issuance has bounced around over the past sixteen years, revenue bonds have remained between 60 percent and 70 percent of new issuance.

To clarify how the number and behavior of municipal bond defaults compare with those of corporate bond defaults, the graphs below plot each series against the Philadelphia Fed’s national coincident index, a proxy for GDP. In the case of corporate bonds, defaults occur at a higher frequency during recessionary periods. In contrast, the pattern of municipal bond defaults appears less tied to recessionary periods. The absence of a clear pattern leads us to believe that municipal bond defaults may be more a function of idiosyncratic factors associated with individual sectors or issues than the result of broad macroeconomic developments.

The second graph also illustrates one of the main points of our post: the untold story of municipal bonds is that default frequencies are far greater than reported by the major rating agencies. Again, this is partly because the rating agencies’ default numbers only cover bonds that they rate, and the unrated portion of the market can be home to municipal bonds of lower credit quality, exhibiting a higher frequency of defaults. Until recently, investors could take some comfort from the fact that many municipal bonds—both rated and unrated—carried insurance that paid investors in the event of a default. But now that bond insurers have lost their AAA ratings, they no longer play a significant role in the municipal bond market, increasing the risks associated with certain classes and certain issuers of municipal debt.

In a coming post, we will explore a municipal bond sector—industrial development bonds—where defaults have been relatively common, highlighting specific examples of defaults.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Lou Manheim's Helpful Links

Lunch is for wimps

It's not a question of enough, pal. It's a zero sum game, somebody wins, somebody loses. Money itself isn't lost or made, it's simply transferred from one perception to another.